By Laura Ieraci

ROME — To be a neighbour has little to do with proximity and everything to do with how one enters into solidarity with another person in need, said Jesuit Father Aloysius Mowe during his recent VPI lecture, titled “Who is My Neighbour?”

Father Mowe, who is the international director for communications and advocacy of Jesuit Refugee Services, was the second presenter in The Lay Centre’s fall faith formation series.

Referring to Scripture, Father Mowe said Jesus explains what it means to be a neighbour in his recounting of the Parable of the Good Samaritan. None of the main characters in the parable are anywhere near their homes. Rather, they are “all people on their way from one place to another,” said Father Mowe in his presentation Oct. 18.

“The parable does not speak of being a neighbour in terms of geography, or of identity, but of action,” he said. “The neighbour is the one ‘who was moved with pity’; the neighbour is ‘the one who showed mercy.’”

He said the “tradition of migration and exile” runs throughout the Bible. Salvation history is the account “of a people in exile and the God who journeys with them in kindness and compassion,” he explained.

Jesus Christ, the Son sent by the Father, also goes into exile. He becomes “the stranger seeking a welcome,” said Father Mowe. Immersed in the sin of the world, Jesus is humiliated, becomes a servant, but is ultimately exalted, he said.

“The experience of exile is at the same time the moment of salvation,” he continued.

Catholic Social Teaching draws on these Biblical themes of covenant and exile. St. John Paul II, in his 2004 instruction “Erga Migrantes Caritas Christi” (“The Love of Christ toward Migrants”), reminded “Christians that they are called to live out the memory of being a community of exile,” said Father Mowe.

“We are spiritual strangers in a foreign land because we belong in the heart of God, where we are placed and which becomes our true home; but in this life, we are not quite there yet, but always a people on the way,” the Jesuit told his listeners.

“Jesus repeats the journey of the people of God in exile, and is always then on the side of the sojourner in another land, the stranger seeking a welcome,” he said.

“Jesus is not like one of these poor,” he continued, “in the most profound solidarity of all, he is one of these poor.”

Father Mowe then share a personal witness: “My own experience and the experience of many of us who have worked with refugees in the most desperate situations is precisely this. When I visited terminally ill refugees in Johannesburg, South Africa, some months ago with a Jesuit Refugee Service nurse, my experience was not that of a priest going in to bring God and consolation to the refugees: I walked into the small, inadequate rooms in crumbling high rises, and what I found was God waiting there for me. Not a God of power and consolation, but a God in covenant with his exiled people, hungry, sick, naked, dying and utterly dependent on the kindness of strangers.”

Citing Pope Francis, Father Mowe said the human person’s “basic disorientation” today is due to their having forgotten that they are a “people who are exiles on a journey.”

“We become settled in what Francis calls a culture of wellbeing…to the point that we are indifferent towards others” and think their suffering “is none of our business,” he said.

The purpose of Catholic Social Teaching, then, is to lead Catholics “toward a willingness to suffer” with those who suffer, said Father Mowe.

“The culture of wellbeing protects us against the sufferings of others; Catholic social ethics seeks a way to take the suffering of others into our own lives,” he said. “Solidarity is really just a recognition… that one’s settled state is an illusion.”

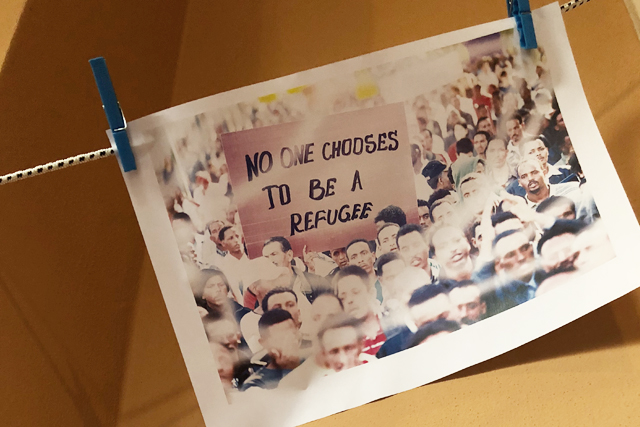

Father Mowe said he refuses the term “refugee crisis” in reference to the millions of displaced people in the world.

“We are not faced with a refugee crisis, but a crisis of solidarity,” he said.

If people are willing to take Catholic Social Teaching seriously, he said, then to be a neighbour “is to be willing to suffer as a form of solidarity. It is to be willing to have one’s standards of living fall so that others may have the means of survival. It is to be willing to have less space, less money, less time, for one’s self, so that one may share life and goods with the vulnerable and the poor.”

Watch the full lecture below: