By Donna Orsuto

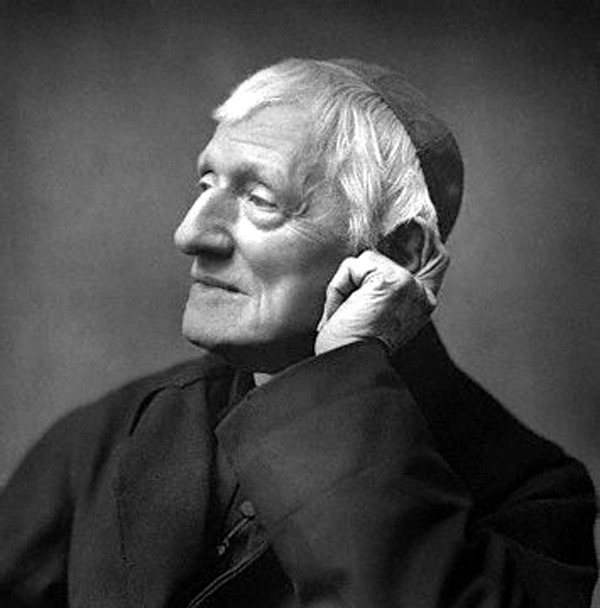

Cardinal John Henry Newman’s commitment to promote an intelligent and educated laity is well known. The English cardinal, whom Pope Francis will canonize this Sunday, was convinced that only a well-formed laity would be prepared to go out into the world and speak convincingly about their faith. He wrote passionately and eloquently on this topic in 1851:

“You must not hide your talent in a napkin, or your light under a bushel. I want a laity, not arrogant, not rash in speech, not disputatious, but men who know their religion, who enter into it, who know just where they stand, who know what they hold, and what they do not, who know their creed so well that they can give an account of it, who know so much of history that they can defend it. I want an intelligent and well-instructed laity... I wish you to enlarge your knowledge, to cultivate your reason, to get an insight into the relation of truth, to learn to view things as they are, to understand how faith and reason stand to each other, what are the bases and principles of Catholicism.”

Newman’s positive vision of the lay vocation and mission in the Church and in society, in the context of the universal call to holiness, in many ways makes him a precursor of the teachings found in the documents of the Second Vatican Council. It is no surprise that Paul VI referred to the Council as “Newman’s hour.”

Today is, more than ever, “Newman’s hour.”

In his writings, Newman offer insights into a spirituality of the laity that supports his vision of an active and articulate laity. One example of this is in a sermon he delivered at the

Requiem Mass for his dear friend James Robert Hope-Scott (1812-1873), and it hinges upon the Scripture passage 1 John 2:17: “The world passeth away, and the desire thereof: but he that doeth the will of God abideth forever.” Newman’s spirituality of the laity is appropriately intertwined with his views on the world and the perennial challenge of how a Christian relates to the world.To put it in simple terms, echoing the title of this sermon: How can a Christian live in the world, and not be of the world?

In this sermon, Newman eloquently speaks of vocation in terms of the responsibility to use one’s talents for others. He says: “we are not born for ourselves, but for our kind, for our neighbour, for our country.” He also acknowledges that “we owe much to those who devote themselves to public life,” but this selfless service is not always easy and often can lead to compromise where one is “obliged to move in a groove” and where at times one can only do “what he feels to be second best.”

Newman does not hesitate to mention that the temptation to “compromise” in the public forum is real. He also honestly acknowledges that a tendency towards “worldliness” plagues all of us, “high and low, national and professional, lay and ecclesiastical.”According to Newman, though, Hope-Scott did not fall into the trap of ambition and worldliness. He was a man of great talent, who, without a doubt, had special opportunities, but who also managed to live this life of service without compromising his faith. Newman notes that Hope-Scott could have lived comfortably, avoiding risks, “giving, but not giving of himself,” yet he chose to live magnanimously.

Listen to Newman’s beautiful description of his friend: “He gave to others without grudging his thoughts, time and trouble. He was their support and stay. When wealth came to him, he was free in his use of it. He was one of those rare men who do not merely give a tithe of their increase to their God; he was a fount of generosity overflowing. It poured out on every side, in religious offerings, in presents, in donations, in works upon his estates, in care of his people, in alms-deeds.”

Newman goes on to mention Hope-Scott’s specific acts of kindness to single women, to sick priests, to families in distress. He explains that it was his friend’s “largeness of mind which made him thus open-hearted.”He also described Hope-Scott as having “a heart always alive and awake at the thought of God,” “a loving desire to please God,” and “a single-minded preference for His service over every service of man.”

All four of these phrases tell us not only about Hope-Scott, but also about Newman’s vision of a holy lay person. He or she is a person who embraces fully the primacy of God and who lives a life poured out in service of others in the midst of social and family commitments.

Newman proposes a lay spirituality of active engagement in the world. He suggests that what enabled Hope-Scott to offer an effective Christian witness in the midst of his worldly responsibilities was the gift of faith. Newman says: “[I]t is the gift of faith, of a living, loving faith, such as ‘overcomes the world’ by seeking ‘a better country, that is, a heavenly.’ This it was that kept him so ‘unspotted from the world’ in the midst of worldly engagements and pursuits.”

Newman encourages his lay friends to embrace their political and social responsibilities, but with their eyes wide open to the challenges that such a life entails. He would also discourage any sort of ghetto mentality of Christianity. Christians have a contribution to make to public service and they will be able to do this only if they have received and cultivated “the gift of faith.”

Donna Orsuto is the director of The Lay Centre and a professor of spirituality at the Pontifical Gregorian University.

The Lay Centre will host a lecture with Rev Dr Ian Ker, Senior Research Fellow Blackfriars, Oxford University, on "The Significance for the Catholic Church of Newman's Canonisation" Dec. 6. Father Ker is considered the world's authority on Cardinal John Henry Newman. For more information, contact info@laycentre.org.

About the text:

This text is a summary of an article by Donna Orsuto, titled, “‘At present, let us do what lies before us’: Some Insights from John Henry Newman for Developing a Spirituality of the Laity,” published in Louvain Studies 35 (2011) pages 384-395.